By Dr. John J. Goyette

Dean, Thomas Aquinas College

Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean Goyette’s report to the Board of Governors at its May 12, 2017, meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks about why the College includes certain texts in its curriculum.

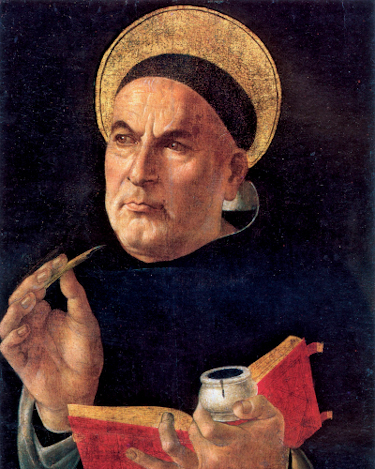

St. Thomas Aquinas is famous for his writing on the Eucharist. He wrote several Eucharistic hymns we use almost exclusively for Eucharistic adoration: “Panis Angelicus,” “Pange Lingua,” “O Salutaris Hostia,” and “Tantum Ergo.” He was commissioned by Pope Urban IV in 1264 to compose the celebratory Mass and the divine office for the newly instituted feast of Corpus Christi. Three hundred years later, the Council of Trent used St. Thomas’ treatment of the Eucharist as a basis for its own doctrinal formulations. Indeed, Thomas is so well known for his writings on the Eucharist that in addition to the title “Universal Doctor,” and “Angelic Doctor,” he is also named the “Doctor of the Eucharist.” At the College, we spend the last two weeks of Senior Theology studying St. Thomas’ treatment of the Eucharist from the Summa Theologiae.

There are, of course, many profound elements of Aquinas’ teaching about the mystery of the Eucharist. He discusses the purpose and fittingness of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the supernatural and miraculous conversion of bread and wine into the true body and blood of Christ (which is called “transubstantiation”), and the miraculous suspension of the accidents of bread and wine after the consecration. There is much to think and ponder about the Eucharist, but I would like to focus on just one element of Thomas’s teaching, the Eucharist as spiritual food.

In John 6, Jesus stuns His followers by saying: “I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.” The disciples begin to question. Jesus says even more shockingly:

Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. (Jn 6:53-56)

The disciples begin to doubt: “Many of his disciples, when they heard it, said, ‘This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?’” (Jn 6:60) “But Jesus, knowing in himself that his disciples murmured at it, said to them, ‘Do you take offense at this? … It is the spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail; the words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life.’” (Jn 6:61-3) According to St. Thomas, Jesus explains that His words are to be taken according to a spiritual meaning, rather than a material meaning. “Our Lord said that he would give himself to them as spiritual food, not as though the true flesh of Christ is not present in this sacrament of the altar, but because it is eaten in a certain spiritual and divine way” (Comm. on John, #992).

What is the difference between spiritual food and material food? Material food restores the strength and vitality of the body by changing into the one who eats it, whereas spiritual food nourishes by changing the person who eats it into Christ himself. When we eat Christ, we do not physically tear his body with our teeth, and digest him in some kind of cannibalistic ritual. It is rather we who are changed by what we receive: It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me. To be clear: St. Thomas is not calling into question the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but explaining what being fed by His true body and Blood means. Spiritual eating is nothing other than being united to Christ by faith and charity. This is the proper effect of the sacrament of the Eucharist.

But doesn’t the recipient of the sacrament materially eat the body of Christ when he takes the host into his mouth and physically chews it up? The answer is no. What I chew with my teeth are the appearances of bread, that is, the “accidents” or “properties” of the bread. Christ himself is invisibly present under the accidents of the bread, but not in a manner that is subject to the actions of my teeth, or the digestive powers of my stomach. Indeed, the Christ that is present substantially under the accidents of bread and wine is Christ’s glorified and impassible body that is in heaven. It would be neither possible nor praiseworthy to eat Christ materially. Indeed, it would be an abomination. Hence, we eat Christ spiritually under the sacramental sign, the material eating of the appearances of bread. Just as the water of baptism is the external sign of an interior cleansing of the soul from sin, so the physical chewing of the host is an external sign of an interior and invisible eating which is nothing other than being united in friendship to Christ Himself who is in heaven.

But the pouring of the baptismal water, and the consumption of the sacramental species of bread and wine, are not merely signs or symbols of some spiritual reality. If they were mere signs or symbols, there would be no difference between what the Catholic Church teaches about the sacraments and the Protestant understanding of the sacraments as mere symbols. The water of baptism is not only a sign of spiritual cleansing, but also an instrument of divine power producing the interior effect. And the accidents of bread and wine are not merely a sign of spiritual food, they provide the sensible medium through which Christ makes himself really and truly present, the sacramental veil beneath which is His body, blood, soul, and divinity.

Understanding the nature of spiritual eating helps us to see why St. Thomas calls the Eucharist the “bread of angels.” Since the angels are united to Christ in perfect charity and in the beatific vision, St. Thomas says that they, too, eat Christ spiritually, and do so in a higher and more perfect way. Indeed, our own spiritual eating in the sacrament of the altar is ordered toward the more perfect spiritual eating that the angels enjoy. The Eucharist is a called the “bread of angels” because it is a foretaste of heavenly fellowship and spiritual eating that the angels enjoy and we look forward to in the life to come.

Near the end of St. Thomas’s life, after completing his treatise on the Eucharist, he was seen praying in the chapel at the Dominican Friary in Naples. His confreres saw him lifted into the air, and heard a voice coming from the crucifix saying, “Thou has written well of me, Thomas, what reward will thou have?” He replied, “Nothing but you Lord.”

St. Thomas Aquinas, pray for us.