Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean John J. Goyette’s report to the Board of Governors at its November 16, 2019, meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks about why the College includes certain texts in its curriculum.

By Dr. John J. Goyette

Dean, Thomas Aquinas College

It is to some degree obvious why we read The Federalist, since it is among the key texts of the American founding. But I would like to provide some more concrete reasons for its inclusion in our curriculum by sketching a few of the key themes. Before I do that, it is probably good to set out a few historical facts.

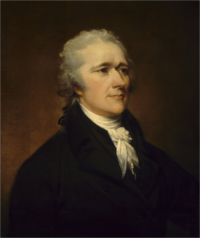

The Federalist was originally published as a series of newspaper articles whose aim was to convince the states to ratify the newly drafted federal constitution. They were composed by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, appearing in print under the pseudonym “Publius,” a name drawn from Publius Valerius, the ancient Roman who helped to establish the Roman Republic. Alexander Hamilton came up with the idea of writing The Federalist in response to published criticisms of the new constitution (by authors later called the Anti-Federalists), which were written under such pseudonyms as “Cato” and “Brutus” (ancient defenders of the Roman Republic). Hamilton invited both Jay and Madison to join the project, but I’m going to focus on Hamilton and Madison since the bulk of the The Federalist was written by them — Jay became seriously ill after composing Federalist #5.

Alexander Hamilton

Let me begin with Alexander Hamilton. A few biographical notes: Hamilton was one of the founders, a protégé of George Washington. As the first secretary of the Treasury, he was responsible for establishing a national bank. Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr, who was the vice president at the time.

Let me begin with Alexander Hamilton. A few biographical notes: Hamilton was one of the founders, a protégé of George Washington. As the first secretary of the Treasury, he was responsible for establishing a national bank. Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr, who was the vice president at the time.

In Federalist #1, Hamilton sets the tone for the series by calling attention to the unique opportunity of the founders to establish a new government by reflection and choice, in contrast to most existing governments, which were founded by force.

Perhaps the most prominent idea that Hamilton promotes is that of a strong executive as provided by the U.S. Constitution. In Federalist #70 he outlines the reasons for this proposition:

Energy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government. It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks; it is not less essential to the steady administration of the laws; to the protection of property against those irregular and high-handed combinations which sometimes interrupt the ordinary course of justice; to the security of liberty against the enterprises and assaults of ambition, of faction, and of anarchy.

In thinking about a strong executive, it is important to have in mind the failings of the Articles of Confederation, which preceded the U.S. Constitution and which were weak and ineffective. Hamilton reminds his readers of the problems with a weak executive: “A feeble Executive implies a feeble execution of the government. A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever it may be in theory, must be, in practice, a bad government.”

Federalist #70 is also famous for defending the separation of powers articulated in the U.S. Constitution. By “separation of powers” I do not only mean a system of checks and balances — one branch of government functioning as a check against the other. Checks and balances are certainly included in the notion of a separation of powers, but Hamilton also insists that the powers separately entrusted to each branch are suitably assigned and delineated in the U.S. Constitution. In Federalist #70, for example, he argues that it is fitting that the executive branch be placed in the hands of a single individual because of the energy required for executive work, whereas the legislative branch ought to have many members, since that makes it more apt to “deliberation and wisdom,” and better able to secure the privileges and interests of the people.

Another key theme in the articles by Hamilton is the principle of judicial review, which specifies the most important role of the judicial branch. He argues in Federalist #78 that the judiciary is responsible for reviewing laws and statutes to ensure that they are consistent with the Constitution. This is among Hamilton’s most important contributions because the Constitution does not explicitly outline any process of judicial review, nor does it specify who has the ultimate authority to judge the constitutionality of laws and statutes. Hamilton argues that to presume that the legislature is the sole judge of the constitutionality of its own actions is to give it an authority that is unchecked. He argues that it is the judicial branch that protects the will of the people as expressed in the Constitution. As Hamilton makes clear, this presupposes that the Constitution is the “fundamental law.” The principle of judicial review was affirmed by the Supreme Court, and articulated in particular by Justice John Marshall, in Marbury v. Madison (1803), arguably the single most important decision in American constitutional law.

James Madison

James Madison

More than any other founder, with the remotely possible exception of Gouverneur Morris, James Madison is responsible for the particular form of government set out by the founders. Recognizing the failings of the Articles of Confederation after the Revolutionary War, he was the principal organizer of the Constitutional Convention and the principal author of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. For this reason he is sometimes called the “Father of the Constitution.”

Along with Thomas Jefferson, Madison was a strong advocate for individual liberties, especially freedom of religion. He served as secretary of state under Thomas Jefferson, during which time he oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, and he later succeeded Jefferson as the fourth president of the United States. It is worth noting that even though Madison collaborated with Hamilton in writing The Federalist, the two later became political opponents because of Hamilton’s efforts to centralize the economy, and they also engaged in published disputation over the use of executive power.

One important respect in which Madison and Hamilton agreed was in their contention that the American founding could not achieve long-term success unless the Constitution were regarded as the “fundamental law.” In Federalist #49 Madison argues for the need to cultivate a reverence for the Constitution and to make amendments infrequent and difficult to enact. Here we see an important difference between Madison and Jefferson. Whereas Jefferson described the Constitution as a “living document” which must keep up with the progress of the human mind, Madison was much less sanguine about the wisdom of frequent change. He saw the need to reverence the Constitution in order to ensure political stability. In this respect, Madison was much more prudent and sober-minded than Jefferson, who is famous for saying that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants” — which he described as “its natural manure.”

Federalist #10 is probably the most famous, and perhaps the weightiest, of the articles of The Federalist. It contains a lengthy discussion of how to address the problem of faction. By faction is meant any group of citizens, whether a minority or a majority, united by some common interest or passion that moves them in a direction contrary to the rights of other citizens or the interests of the whole community. The rich and the poor are perhaps the most obvious examples of political faction.

Previous statesmen and political philosophers sought to reduce or eliminate the causes of faction. For example, they proposed ways in which law and public policy could maximize the size of the middle class and minimize the number of those who are extremely rich or extremely poor, so as to reduce competing class interests. They also sought to produce a uniformity of habits and opinions by some form of common education so that common interests would prevail over private interests.

Madison rejects this line of thought. He argues that any attempt to reduce the causes of faction would either eliminate human freedom (in which case the remedy would be worse than the disease), or would be foolish and impractical. This is because — as Madison puts it — the seeds of faction are sowed into the very nature of man; they arise from “[t]he diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate.” Since Madison regards the protection of these diverse faculties or abilities as “the first object of government,” any attempt to make human beings equal by force or artifice, or to radically curtail the property rights that follow from differing abilities, would necessarily eliminate human freedom. Socialism is one example of how the attempt to eliminate the natural inequality in the ability to acquire property undermines human freedom.

In any case, if we presume that the chief end of government is to protect the natural faculties of acquiring property, then Madison sees faction as a necessary result:

From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of differing degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties. … [T]he most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property.

Madison sees faction as something that cannot be avoided because it flows from the natural and unequal faculties of acquiring property. Efforts to overcome the causes of faction would undermine liberty. Moreover, since unequal faculties of acquiring property necessarily produce “different interests and parties,” attempting to overcome the causes of faction by common education is bound to fail because faction is rooted in natural inequality.

According to Madison, the only remaining alternative is to control the effects of faction. The solution to the problem of faction is contained in the very form of government that is proposed by the U.S. Constitution, that is, a democratic republic. Here we must distinguish between a pure democracy — a society consisting of a small number of citizens who meet in person to deliberate and administer the government — and a republic or representative democracy — a political society where the people are sovereign, but government is administered by a small number of elected officials.

Madison sees two distinct advantages of a democratic republic. First, by placing the powers of government in the hands of a few elected officials, the odds are greater that those who rule will have a great wisdom to discern the true interests of the people and a love of justice that will make them less likely to be swayed by partial or temporary interests. In short, the interests and opinions of the people will be refined and enlarged by passing them through the medium of elected representatives. Second, a representative democracy can include a greater number of citizens and be spread over a much larger territory, which, according to Madison, is the principal advantage of republican government. The greater the sphere, the greater the number of parties and interests, which will make it less probable that any one party or interest will dominate.

In other words, the solution to the problem of faction is to multiply the number of factions! By increasing the number of factions, you can decrease the probability that any one faction will prevail over the interests of the others. While Madison recognizes that no form of government can prevent an unjust majority from overthrowing the rights and interests of the minority, he argues that republican government, and more particularly an extended republic, is the form of government that best safeguards liberty against the tyranny of the majority.

Thus we can see that, even though the articles of The Federalist were written in response to address a very particular historical moment, they address perennial themes about the nature of government, of man, of freedom and equality. These themes underlie almost every political debate, irrespective of time or place, and understanding them is essential for any American and all true lovers of liberty.