Why We Study Dostoevsky

By Dr. Brian T. Kelly (’88)

Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean Brian T. Kelly’s report to the Board of Governors at its February, 2012, meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks in which Dr. Kelly explains why the College includes certain authors in its curriculum.

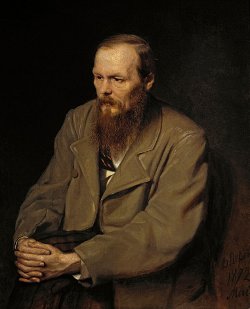

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) was orphaned as a teenager, served in the military, and flirted with utopian socialism. Because of this last entanglement he was arrested and condemned to death. Clemency was granted, but he still served hard time in Siberia, where he drew closer to his Orthodox faith. He traveled extensively, gambled his way into deep and troublesome debt, and developed epilepsy. He edited political and literary journals and somehow also found time to publish critically successful and popular novels, including Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and Notes from the Underground. By the time he completed The Brothers Karamazov, his final work, he was recognized as one of Russia’s premier writers. He died shortly after completing this novel.

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) was orphaned as a teenager, served in the military, and flirted with utopian socialism. Because of this last entanglement he was arrested and condemned to death. Clemency was granted, but he still served hard time in Siberia, where he drew closer to his Orthodox faith. He traveled extensively, gambled his way into deep and troublesome debt, and developed epilepsy. He edited political and literary journals and somehow also found time to publish critically successful and popular novels, including Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and Notes from the Underground. By the time he completed The Brothers Karamazov, his final work, he was recognized as one of Russia’s premier writers. He died shortly after completing this novel.

The Brothers Karamazov is a towering epic, close to 800 pages long and brimming with passionate, vibrant prose. It is full of philosophy, theology, poetry, turgid emotion, and violent melodrama. It even turns into a bit of a murder mystery.

The histrionics revolve around the highly dysfunctional Karamazov family, including Fyodor Pavlovich and his three, or possibly four, sons. Fyodor’s cook, Smerdyakov, the son of a homeless retarded girl, appears also to be Fyodor’s son. Norman Rockwell would not be interested in doing a family portrait, though Jerry Springer would happily book them for his show. Dmitri, the oldest, is passionate and irresponsible. Ivan is abstract and rational. Alyosha, the youngest, is gentle and kind and very much in love with Christ. He thinks he has a vocation to the local monastery, but Fr. Zossima, his saintly spiritual director, sends him back into the world.

I will not summarize the whole novel. I am too afraid of ruining the story for you. It is great. Instead I will discuss what I take to be the two great and warring ideas lying at the heart of the tale. The first great idea is that, as sons of God, all men form a community. This could be called the idea of universal Christian brotherhood or, more simply, the Christian ideal. The second great, though not quite as great, idea is that God is either dead or irrelevant and therefore there are no moral rules. I think it is fair to call this idea Nietzschean nihilism even though it predates Nietzsche’s articulation of the will to power.

The story revolves around Alyosha, who believes in the first idea. Alyosha loves everyone, and everyone is drawn to him. He has learned from Fr. Zossima that “each of us is guilty before everyone and for everyone.” This is an odd saying and it sounds vaguely false, but it dominates much of the book and is, therefore, worth examining closely. What does it mean and is it really the Christian ideal?

In his reckless youth Zossima challenged an innocent man to duel over a woman. The night before the duel he became angry with his manservant, Afanasy, and struck him in the face. All night he tossed and turned and couldn’t comprehend why. In the morning he rises from his bed as though thunderstruck. It is not the coming duel that is tormenting him, but the fact that he has struck his servant. He says, “this is what a man can be brought to, a man beating his fellow man! What a crime! It was as if a sharp needle went through my soul. This question then pierced my mind for the first time in my life. ‘Mother, heart of my heart, truly each of us is guilty before everyone and for everyone.’”

It is hard here to know exactly what he means when he says that each of us is guilty before everyone and for everyone. But it is clear that it turns on the realization that God has made all of creation to praise and serve Him, and that all men are created in the image and likeness of God. It is in some way a realization that as a Christian everyone is my neighbor.

Fr. Zossima says later, “There is only one salvation for you: take yourself up, and make yourself responsible for all the sins of men.… Remember especially that you cannot be the judge of anyone.” Here it is evident that he aims at imitating Christ’s willingness to suffer for all, but with the clear recognition that he can in no way supplant Christ so as to be the judge of others.

But even if this is an attempt at the Christian ideal, what if it is not true? If he really isn’t guilty before all and for all, then this is a false imitation of Christ. Isn’t it obvious that the Christian is not guilty for the sin that his neighbor commits? Christ certainly spoke of good and bad servants as though they each were responsible for their own actions. Isn’t it a lie to suggest that the good servant is guilty for the bad servant?

Fr. Zossima sheds a little light on the claim later in the story when he says, “If the wickedness of people arouses indignation and insurmountable grief in you … fear that feeling most of all; go at once and seek torments for yourself, as if you yourself were guilty of their wickedness.”

Here the “as if ” makes it clearer that he is recommending a practical approach and not teaching a moral truth. It’s like the advice “The customer is always right,” or “work as if everything depends on you and pray as though everything depends on God.” It is not strictly true that the customer is always right or that everything depends on you, but the advice can be helpful all the same. So when Fr. Zossima says, “each of us is guilty before everyone and for everyone,” he is preaching an attitude of openness to the sinner and to accepting suffering on the sinner’s behalf, a common theme among the doctors and fathers.

Fr. Zossima insists that in a certain way we do share the sinner’s guilt. He says, “understand that you, too, are guilty, for you might have shone to the wicked even like the only sinless One, but you did not. If you had shone, your light would have lighted the way for others, and the one who did wickedness would perhaps not have done so in your light.”

This is an important realization, that no man sins in a vacuum. When your brother sins in your sight you may very well have contributed to his sinful action by failing to give him the appropriate example when you didn’t imitate Christ, “the only sinless One.” Your neighbor’s sin is his, but you contributed by falling short before him.

God calls us to “be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect.” At best we respond imperfectly. When we recognize this in ourselves, we can resist pride and be more loving and humble with our brother. For Fr. Zossima this is the proper way to approach the sinner. This is the way to win the sinner to Christ. You may be scratching your head at this point. This sounds good, but how does it fit with what is most touted about The Brothers Karamazov? Of all of the parts of this massive book, it is the chapter called “The Grand Inquisitor” that is the most famous and most frequently read.

In the preceding chapter Ivan recounts a litany of cruel and senseless sufferings inflicted by human beings, mostly on children. Dwelling on these Ivan declares that there is no God, or if there is he does not want to know Him. In “The Grand Inquisitor” Ivan tells a story he has written in which Christ returns to earth to find that his brave attempt to rescue mankind by dying on the Cross has failed. His solution was too much out of tune with the reality of the human condition. Mankind is too frail to accept Christ’s unreasonable offer of sanctifying grace.

In his rejection of God, Ivan can see no rational basis for morality. This is the second idea that we called earlier a version of Nietzschean nihilism. Ivan and his philosophy stand in total opposition to Fr. Zossima and Alyosha. As if to make this perfectly clear, Ivan admits, “I never could understand how it’s possible to love one’s neighbors. In my opinion it is precisely one’s neighbors that one cannot possibly love.”

The Brothers Karamazov is widely recognized as a great philosophical novel. It raises the enduring questions about God, suffering, and the human condition. It does not gloss over man’s wickedness and it gives the heathen full and fair opportunity to rage. And it presents the two great options, which Bl. John Paul II named the Culture of Life and the Culture of Death.

Without giving away the ending I will suggest that the action of the story suggests clearly which is the way of health and hope and love, and which is the pathway to despair, mental sickness, and spiritual death. The wisdom of The Brothers Karamazov is very modern and very ancient. It is indeed a great philosophical novel, but even more it is a great Christian novel.