Why We Study St. Thomas Aquinas

By Dr. Brian T. Kelly (’88)

Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean Brian T. Kelly’s report to the Board of Governors at its May 11, 2012, meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks in which Dr. Kelly explains why the College includes certain authors in its curriculum.

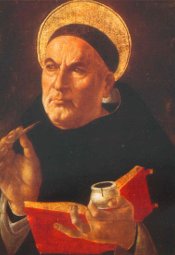

St. Thomas Aquinas needs no introduction. He is our patron and mentor, our muse and our intellectual master. We love to talk about him and his decisive role in the construction and execution of our curriculum. From the very beginning it was so, and so it will remain until the good Lord decides our time is up.

Why is he so central to us? The answer simply put is that we are aiming to educate under the light of Catholic wisdom, and Thomas, more than anyone else, represents the pinnacle and synthesis of Catholic wisdom. He is the patron of Catholic schools and students. He has been named the Common and Universal Doctor and singled out for preeminence by an unbroken succession of popes since shortly after his death. It is remarkable to consider how highly and consistently the popes have praised him and the importance of his thought. Even our current pope, who before his accession to the throne of Peter was reputed to favor St. Augustine over St. Thomas, has echoed the endorsements of his predecessors in his Wednesday Audiences (for example, June 2, 2010).

While Thomas’ teaching and writing are of vital importance, I hope to speak about them another day. Today I want to go a little deeper and talk about his spirituality. For his teaching and writings were the fruit of his complete devotion to the one who is the Way, and the Truth, and the Life. They have been a priceless gift to the Church and crucially formative for our own endeavor, but for Thomas they were secondary. We see this in a powerful way from a story told about Thomas near the end of his life. While saying Mass on the feast of St. Nicholas in 1273, Thomas was granted a vision of Heaven. He immediately discontinued all of his writing projects, including his great Summa Theologiae, which remains unfinished. He said that all of his writings seemed “like straw compared to what has now been revealed to me” (The Life of St. Thomas Aquinas, Foster, p. 110).

Today I want to address three aspects of St. Thomas’ spirituality: his commitment to truth, his life of prayer, and his humility. Any attempt at an accurate portrait of St. Thomas the man must in some way address these three themes.

St. Thomas’ Spirituality

Thomas saw that all being, and thus all truth, flows from God’s creative hand. He lived in wonder and in a dogged pursuit of the truth, not merely because it is natural to desire knowledge, but also because all learning is drawing closer to God. This devotion to truth can be seen in his daily schedule. Many witnesses at his canonization inquiry testified that, aside from prayer, his time was almost completely devoted to study. There are famous stories of Thomas lost in contemplation, insensitive to his surrounding, even when at table with the king of France. He longed for, pursued, hunted truth. Once while praying in the Dominican chapel in Naples, a friend from Paris named Romanus walked in to speak with him. Romanus revealed that he had died two weeks earlier but had been allowed to visit to reward Thomas’ merits. Thomas recognized an opportunity when he saw one, so he proceeded to quiz Romanus on the mechanics of the beatific vision.

His devotion to God’s truth can also be seen in his rejection of all deliberate falsehood, and in the submission of his writings to the correction of the Church.

Thomas’ love of truth and his great learning and wisdom were organically linked to our second theme, his life of prayer. He advanced far in learning partly because he was intelligent and well-educated, but mostly because he pleaded so earnestly with God to illuminate him. Bernard Gui, one of his earliest biographers, reports that “he never set himself to study or argue a point … without first having recourse inwardly — but with tears — to prayer for the understanding and the words required by the subject. When perplexed by a difficulty, he would kneel and pray and then, on returning to his writing or dictation, he was accustomed to find that his thought had become so clear that it seemed to show him inwardly, as in a book, the words he needed” (p. 37).

In one extreme case Thomas was stumped by a difficult passage from Isaiah. For several days he prayed and fasted begging God to shed some light on the mind of the prophet. One night he stayed up late praying in his cell. From outside his secretary, Reginald, heard him conversing with what sounded like two other voices. When the voices grew quiet Thomas called to Reginald and proceeded to dictate a clear and thorough interpretation of the passage. After much and insistent entreaty, Thomas admitted that the two voices were those of Sts. Peter and Paul, sent to answer his prayer.

Bernard says, “In Thomas the habit of prayer was extraordinarily developed; he seemed to be able to raise his mind to God as if the body’s burden did not exist for him” (p. 36-7). Thomas did not turn to prayer only in time of need; he lived his life in constant communion with God. He was especially mindful of God’s presence in the Holy Eucharist. Each morning he would say one Mass and attend another before turning to his scholarly activities. Many witnesses for his canonization tell of this daily practice and of the tears he would frequently shed at the reception of God’s body and blood. At other times he could often be found in the chapel with his head resting on the tabernacle. His love for Christ in this sacrament is manifest in his Eucharistic hymns, especially O Salutaris Hostia, Adoro Te Devote, the Pange Lingua, and the Tantum Ergo. These are still some of the most beautiful hymns ever written, and they flowed from the heart of a man who is often caricatured as living among dry abstractions.

His heart was full of Christ. There are many beautiful stories that show this. He became quite fearful in thunderstorms but would remind himself that “God came to us in the flesh; He died for us and rose again” (p. 53). So he knew where to turn when things got tough.

When he had completed his treatise on the Eucharist, Thomas brought the text and placed it at the foot of the crucifix. An old lay brother, Dominic of Caserta, saw Thomas deep in prayer gazing at the crucifix and “heard a clear voice say these words: ‘You have written well of me, Thomas; what do you desire as a reward for your labours?’” (p. 42-3). Thomas replied: “Nil nisi te,” which means, “Nothing except for you.” This attitude can also be seen even at the very end of his life when he was given Holy Communion for the last time, and he exclaimed, “[I receive you] O price of my redemption and food for my pilgrimage. For your sake I have studied and toiled and kept vigil” (p. 55).

Our consideration of Thomas’ constant life of prayer and communion with Christ leads us to our third theme, his humility. Bernard says that Thomas’ humility was a reflection of his desire to imitate the Master, to be Christlike in all things (p. 48). You have heard of the man who was proud of his humility; Thomas was just the opposite. He was honest enough to know that he was humble, but he attributed this to a gift from God, and gave earnest thanks for being preserved from conceit.

Submission to God and One Another

I would like to finish with two brief stories: Once when Thomas was visiting the Dominican House of Studies in Bologna he was wandering the grounds of the priory deep in contemplation. Now the prior had given another visiting brother permission to take the first man he should meet as his helper for the day. So when he bumped into Thomas, he immediately put him to work, completely unaware of whom he was ordering around. Because Thomas was slow of foot, he suffered many hard words, always without protest. When others witnessed this they rushed to inform the visitor of Thomas’ identity. The visitor was mortified at his mistake and profusely apologized. But Thomas gently reminded them that the way to perfection must be obedience. He added that “if God … had humbled himself for our sake, should not we submit to one another for God’s sake?” (p. 49).

Years later when Thomas was lying ill on his deathbed at Fossanova, it was very cold and so the monks carried logs in to keep a fire burning to help him stay warm. Thomas became distressed and was heard to say several times, “Who am I that the servants of God should wait on me like this?”

St. Thomas Aquinas, patron of our school, keep us humble, prayerful, and in love with God’s truth.