- Home

-

About

Fidelity & Excellence

Fidelity & ExcellenceThomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

-

A Liberating Education

Truth Matters

Truth MattersTruth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

-

A Catholic Life

Under the Light of Faith

Under the Light of FaithThe intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

-

Admission & Aid

Is TAC Right for You?

Is TAC Right for You?Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

-

Students & Parents

Mind, Body & Spirit

Mind, Body & SpiritThere is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

-

Alumni & Careers

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Search

- Giving

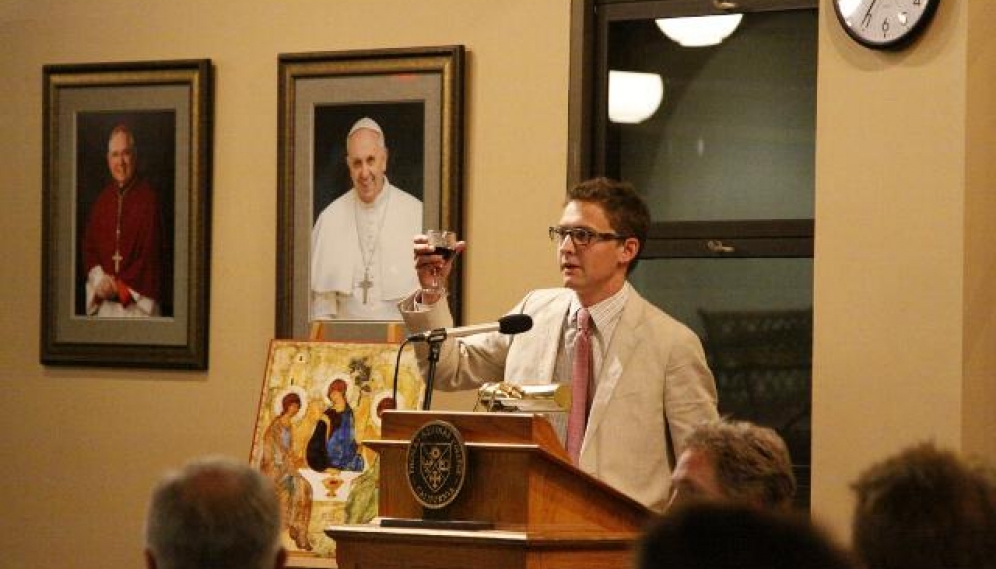

The President’s Dinner 2015: Remarks and Slideshow

Note: Each year the president of Thomas Aquinas College hosts a dinner on the Wednesday before Commencement as a chance for members of the faculty and staff to bid farewell to the graduating class. The president, dean, and assistant dean all speak to the Seniors and, customarily, the Seniors present a gift to the College. Below are President Michael F. McLean’s remarks and a photographic slideshow from this year’s dinner.

Address to the Class of 2015

By Dr. Michael F. McLean

President, Thomas Aquinas College

May 13, 2015

The idea for this talk came from one of those obscure, but great, articles in St. Thomas’s Summa Theologiae. In Part I of the Second Part, Question 40, he asks “whether hope abounds in young people and those who love drink?” (Utrum in iuvenibus et ebriosis spes abundet?) The title alone promises that this will be one of the best articles in the Summa.

Despite the fact that you are young people and that you are enjoying moderate amounts of wine to celebrate your upcoming graduation, I will ignore, at least this evening, the “drink-loving” part of the article and focus on your youth and the hope that St. Thomas says “abounds” in you.

Hope is characteristic of the young, says St. Thomas, because it has for its object a good which is future, arduous, and possible. You have much of the future before you, and relatively little of the past, and since memory is of the past and hope of the future, you have rather little to remember and much to hope for. Likewise, you possess an abundance of energy and spirit and so you are anxious to pursue the arduous and difficult. Finally, for you all things are possible because you have suffered few defeats. You are rightly full of confidence because you have relatively little experience of your shortcomings.

Soon you will leave Thomas Aquinas College and enter a world which places its hope in progress. First of all, a hope in scientific and technological progress rooted “in the foundations of the modern age,” as Pope Benedict XVI wrote in his great encyclical Spe Salvi (loosely translated as “On Christian Hope”). Benedict points specifically to Bacon’s Novum Organum, with its promise of “the triumph of art over nature … and a new correlation between science and praxis.” Reliance on science and technology alone, and a consequent hope in their possibilities, has become deeply rooted in modern man.

Likewise, trust in scientifically based politics and a hope of creating a perfect world has become rooted in man, inspired in no small part by Marx’s critique of political economy and his call to revolution. As I am sure you know, progressivism in politics and morals is rampant today and, among other things, manifests itself in relentless attacks on the natural law and Catholic moral teaching.

As Benedict points out, however, and as you must remember, modern hope is inherently inadequate. Human freedom is always an obstacle to utopia; science and politics can both be misused, as recent history so clearly proves. Moral relativism is not enough; there is need for an unshakable moral criterion if science and politics are to be of true benefit to man.

One of your tasks as you enter the modern world, says Benedict, is to do what each generation must do — as he puts it, “you must discover the ethical for yourself.” He does not mean that you must invent the ethical for yourself. Rather, you must apply anew the universal principles of morality and virtue to your particular situation and to the challenges you will confront.

Or, as Pope St. John Paul II put it in his book Crossing the Threshold of Hope: “What is youth? It is not only a period of life that corresponds to a certain number of years, it is also a time given by Providence to every person and given to him as a responsibility. During that time he searches, like the young man in the Gospel, for answers to basic questions; he searches not only for the meaning of life but also for a concrete way to go about living his life … the young are searching for God … they are searching for definitive answers [to the question]: ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’ This is the most fundamental characteristic of youth.”

It is not enough that your hope, like modern hope, be grounded in reason alone. To find a secure moral foundation, and to find the answer to the young man’s question, requires that faith inform reason just as reason must inform faith — always faith and reason together, working in harmony.

To be sure, says Benedict, “you need the greater and lesser hopes that keep you going day by day.” You need to hope for marriage, for children, for friendship, for a profession, for a vocation, and that you will be generous to your alma mater after you have made your fortune. Or perhaps this latter is something we should hope for. Be that as it may, these all are natural goods, necessary for happiness and human fulfillment.

But faith brings with it “the great hope that sustains the whole of life … man’s great, true hope which holds firm in spite of all disappointments can only be God — God who has loved us and who continues to love us ‘to the end … until all is accomplished.’”

The hope of the believer is the hope for eternal life, and “this is eternal life — that they know you the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.”

Your years at the College have prepared you well to commence … to commence with “the great, true hope” that will withstand all of the vicissitudes of life.

First, as readers of Bacon, Marx, and other great modern authors, you are in an excellent position to see the true strengths and weaknesses of modernity and its hopes — to shun the illusory and to rest confidently and hopefully in the real.

Second, you have learned from St. Thomas to respect the universality of the natural and divine laws and to habitually search for the harmony between faith and reason. This is what the study of St. Thomas is all about — to prepare you to undertake your personal search for the ethical from a firm and principled foundation and to “always be ready to give a reason for the hope within you.”

Third, you have enriched your spiritual lives and deepened your relationships with Christ — abiding in Him, your hope in eternal life can truly abound.

Finally, with Christ at your side, you will have ever before you a model of One who “died for all, that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for Him who for their sake died.” To live for Christ, Benedict says, means allowing yourselves to be drawn into His being for others.

As a consequence, this will require you to join the saints in their tireless love of neighbor. To take but one example: St. Augustine, embracing a totally new life after his conversion, said of the tasks before him: “The turbulent have to be corrected, the faint-hearted cheered up, the weak supported; the Gospel’s opponents need to be refuted, its insidious enemies guarded against; the unlearned need to be taught, the indolent stirred up, the argumentative checked; the proud must be put in their place, the desperate set on their feet, those engaged in quarrels reconciled; the needy have to be helped, the oppressed to be liberated, the good to be encouraged, the bad to be tolerated; all must be loved.”

Grounded as they are in fallen human nature, and in the circumstances of our time, these tasks are as much yours as they were Augustine’s.

Considering this list, and the Christian life in general, Augustine said “the Gospel terrifies me.” So should it, in a sense, terrify us all. But this is the fear that is the beginning of wisdom. You can take great consolation in the fact that your duties as followers of Christ are set before you — that your path as sons and daughters of the Church is clearly marked and will be so marked no matter what claims, true or false, are made in the name of “progress.”

Relying on God’s abiding love and grace, striving to fulfill your duties and to stay on that path humbly and charitably, being not afraid, you can be certain as you leave Thomas Aquinas College that your greatest and most profound hopes will surely be realized.