- Home

-

About

Fidelity & Excellence

Fidelity & ExcellenceThomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

-

A Liberating Education

Truth Matters

Truth MattersTruth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

-

A Catholic Life

Under the Light of Faith

Under the Light of FaithThe intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

-

Admission & Aid

Is TAC Right for You?

Is TAC Right for You?Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

-

Students & Parents

Mind, Body & Spirit

Mind, Body & SpiritThere is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

-

Alumni & Careers

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Search

- Giving

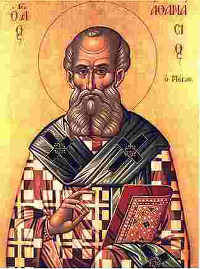

The Father of Orthodoxy: Why We Read Athanasius

By Dr. Brian T. Kelly (’88)

Dean, Thomas Aquinas College

Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean Brian T. Kelly’s report to the Board of Governors at its November 12, 2016, meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks about why the College includes certain texts in its curriculum.

Athanasius, saint and doctor of the Church, stands out on the pages of Church history as the greatest champion of the mystery of the Incarnation. Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Word, is truly God and truly man. He is one person with two natures. From the beginning this was a hard saying. Though there were many conflicting heresies concerning Christ’s divinity and humanity, Hilaire Belloc labels Arianism as “the first great heresy,” and calls it “the summing up and conclusion” of all of its predecessors.

Belloc also says, “it has been the fashion to laugh at the Arian affair as though it were an almost incomprehensible and certainly ridiculous dialectical quarrel; hair-splitting and word-juggling. It was enormously more than that. It was a whole perverted aspect of the Catholic Church, affecting a great body of the hierarchy, established like a parasite within the organism, and threatening to starve and ultimately destroy its life. For Arianism was essentially the rationalizing spirit — that is, the inability to see that there are things beyond reason … It was the spirit that asked of the Mysteries, ‘How can such things be?’”

The Arian heresy emerged at a very crucial and vulnerable time for the Church. It came shortly after the brutal persecution of Diocletian and the edict of Milan. Christianity was now in favor with the Roman emperor Constantine but not very firmly established in the fabric of the empire. There were many issues that needed to be worked out concerning the balance of power between papal, imperial, and episcopal authorities.

Seeing that the Arian heresy threatened the unity of the Church and empire, Constantine called the bishops of the world to come together for a council in the eastern city of Nicaea in 325. This was the first ecumenical council since the Council of Jerusalem described in the Acts of the Apostles.

This council produced a statement or “symbol” of faith that provides the basis for the creed that we recite at Mass every Sunday. This was carefully crafted to capture the basic beliefs of the Church and to unambiguously refute the teachings of Arius. Central to this was the crafting of a Greek philosophical term homoousios, which is translated as “consubstantial” or “one in substance.”

Athanasius, a young deacon assistant to the patriarch of Alexandria, proved very influential in the discussions among the council fathers because of his clarity, orthodoxy, and spirit. Shortly thereafter he succeeded Alexander as Archbishop of Alexandria at the very young age of 30.

As the adherents of Arius insinuated themselves into positions of influence in the imperial court, they labored to reestablish Arius and others in respectable ecclesiastical appointments. They even persuaded Constantine that Arius’ position had been misrepresented, and the emperor requested that the young archbishop accept the heretic back into full communion with the church of Alexandria.

Athanasius remained intransigent and soon found himself summoned before, and condemned by, a kangaroo court of hostile bishops. For the next 40 years he bore the brunt of all the venom of the heretical party and was the last best hope of the orthodox. He was exiled on five different occasions from his see, and for several years lived in hiding. Various weak popes supported him and strong emperors opposed him. One episcopal court even accused Athanasius of murdering a priest. As evidence of his crime they produced a severed hand. As evidence of his innocence, Athanasius produced the “murder victim,” alive and well. The Arian faction was so strong that at times it truly seemed that it was Athanasius against the whole world, Athanasius contra mundum. But the faithful in Alexandria never forgot him. When the Emperor tried to replace him, the people stoutly refused to accept anyone but Athanasius. He knew his sheep, and his sheep knew him.

By his words, deeds, and sacrifices in defense of the Incarnation, Athanasius earned the title “father of orthodoxy.” How fitting then that our sophomores read his youthful treatise, De Incarnatione Verbi Dei. It is a short but marvelous work explaining why the Word was made flesh, and providing persuasive apologetics against the claims of the Jews and the Gentiles.

I want to say just a few brief words about a central concept of this treatise, i.e. the divine dilemma.

God created man out of gratuitous generosity. He made us in His image as an expression of the mind of God, and put us in the garden with one prohibition only. We were forbidden to eat fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and if we fell, the punishment, death and corruption, was clear.

Well, you know the rest of the story. Having been given everything, we could not resist the one thing that was not allowed.

Where did that leave us? “Under the natural law of death … No longer in paradise, but dying outside of it” (On the Incarnation).

Where did this leave God? According to Athanasius, this left God in a trap, which he calls the divine dilemma. There is no escape for man from the demands of divine justice. God cannot retract his words that man must die. But how “monstrous and unfitting,” he wrote, that God’s handiwork, the expression of his own mind, should come to nothing. What was the use of having made man if he was only to perish?

This is the trap: God cannot simply forgive and forget, and on the other hand He cannot allow man to pass into nothingness. To preserve the “divine consistency,” man must die and man must not die.

How did God escape from this great perplexity? This is where the Incarnation comes in. To quote Athanasius:

For this purpose, then, the incorporeal and incorruptible and immaterial Word of God entered our world. He saw … the race of men that like Himself, express the Father’s mind, wasting out of existence, and death reigning over all … He saw too how unthinkable it would be for the law to be repealed before it was fulfilled. He saw how unseemly it was that the very things of which He Himself was the artificer should be disappearing. He saw how the surpassing wickedness of man was mounting up against them; He saw also their universal liability to death … And pitying our race, moved with compassion … He took to himself … a human body even as our own ... He took it directly from a spotless, stainless virgin, without the agency of human father ... As a temple for Himself … He surrendered His body to death in place of all and offered it to the Father. This He did out of sheer love for us, so that in His death all might die, and the law of death thereby be abolished.

The Word of God solved the great and divine dilemma by Himself paying the price of redemption. The divine man died so that feeble man might live.

St. Athanasius, great spiritual warrior in troubled times, pray for us.