- Home

-

About

Fidelity & Excellence

Fidelity & ExcellenceThomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

-

A Liberating Education

Truth Matters

Truth MattersTruth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

-

A Catholic Life

Under the Light of Faith

Under the Light of FaithThe intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

-

Admission & Aid

Is TAC Right for You?

Is TAC Right for You?Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

-

Students & Parents

Mind, Body & Spirit

Mind, Body & SpiritThere is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

-

Alumni & Careers

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Search

- Giving

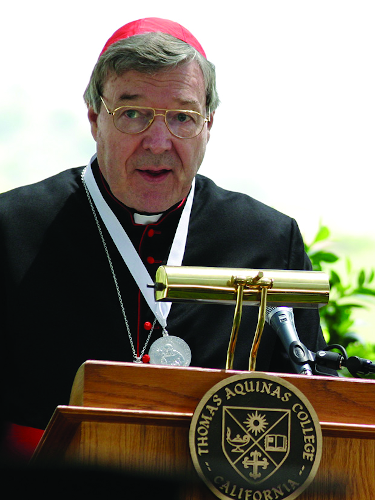

Cardinal Pell: “A Life Characterized by Wisdom, Learning, Courage, and Holiness”

His Eminence George Cardinal Pell

Archbishop of Sydney

Commencement Address to the Class of 2008

President Dillon, members of the Board, graduands, students, faculty, family, and friends:

President Dillon, members of the Board, graduands, students, faculty, family, and friends:

I would like to thank the College for the honor of being awarded this Saint Thomas Aquinas Medallion. I am touched by the honor and the award, especially when I look at the list of previous recipients.

Like your president, a number of you have said that I have come quite a distance. I have come because for years I have known about Thomas Aquinas College, and I value deeply the work that is being done here. My visit is a sign of my own personal support for the staff, the students, for all the families, the benefactors, all those who, combined, continue this marvelous work.

An Unusual Advantage

It is always a privilege to deliver a Commencement Address to a group of new graduates, to congratulate them on their achievements, and to thank their families, sponsors, benefactors, and friends who supported them during their studies. We look forward with Christian hope and human optimism to the contribution they will make to society and the Church in the future.

As I mentioned, I have long been an admirer of St. Thomas Aquinas and as the president mentioned, for eleven years I headed Aquinas College in Ballarat, Australia, which is now a campus of Australian Catholic University. But unfortunately my Aquinas College was not a Great Books college. I believed so much in what you were doing that, in fact, I tried to interest the Australian Catholic University in running a Great Books program within the university, but unfortunately I was completely unsuccessful in persuading a sufficient number of the faculty.

Students here — and I think they realize this — have an unusual advantage from their direct engagement for four years with the profound thinkers who have shaped our Western civilization. They have followed the traditional Socratic method of questioning and dialogue, and continued their search for meaning and truth in a learning institution which is committed explicitly to the Catholic faith. Faith and reason are offered for their acceptance or rejection as they rigorously examine the intellectual claims of these great authors, religious or otherwise.

I congratulate the Senior Class Speaker, Joseph Thompson, who spoke on their behalf. What he said boded well — very, very well — for the quality of the learning that they have undertaken here. So, I repeat that they — the graduates and the students here — are unusually blessed and advantaged, because they have an ideal base for any professional course at all that they might now choose to pursue, any course whatsoever. And, of course, they have a wonderful base for married life.

St. John Fisher

A commencement ceremony is a happy time. Why then should I choose to speak of an obscure sixteenth century bishop from England, who spent his entire life in Rochester, which was the poorest diocese in England, and then so misjudged the political situation that he was executed by his king on some theological point of principle, without the support of even one of his fellow bishops?

St. John Fisher's story is told simply. Born in Yorkshire in 1469, one of four children to a prosperous merchant, he went to Cambridge University at the age of 14 where he was introduced to the currents of intellectual reform then springing from the Renaissance on the continent. In 1491 he was ordained a priest, gained his M.A., and was elected a fellow of Michaelhouse.

An appointment which was to prove crucial for his later career occurred when he became confessor to Lady Margaret Beaufort, the devout mother of Henry VII. Probably as a result of her patronage, he was appointed Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University in 1501, and in 1504, at the age of 35, he became Chancellor at Cambridge, an office which he held for the rest of his life.

Differences with King Henry VIII

Even in his early years he clashed mildly with the new King Henry VIII, who wanted to take the money his grandmother, Lady Margaret, had bequeathed for the development of new colleges at Cambridge; this greedy king had wanted to use it for his own purposes.

Luther's Protestant Reformation had started in 1517, a development which Henry VIII strongly opposed, even earning from the Pope for himself and his successors to this day the title of "Defender of the Faith" for his defense of the seven sacraments.

Fisher became the best-known defender of Catholic doctrine, and he was selected by Cardinal Wolsey, then Lord Chancellor, to preach at an open air rally outside St. Paul's Cathedral in London against Luther, when Luther's books were publicly burnt in 1526. Henry VIII was so pleased with Fisher's two-hour address delivered in English (which was then a primitive language, quite some years before Shakespeare, and not spoken outside England) that he ordered it to be translated into Latin so that it could be read and understood in continental Europe.

This united front — Henry and the Catholics — was broken by the inability of Henry's wife, Catherine of Aragon, to produce a male heir and Henry's infatuation with the formidable Anne Boleyn, who was eventually also executed by her tyrant husband. A good historian of the period claimed to me that a major reason for Henry's determination to eliminate Anne was his resentment at her bitter hostility to both Fisher and Thomas More.

We all know that Henry wanted his first marriage to be annulled, that this was refused by Rome, so that he responded by declaring himself to be head of the Church in England. After careful study, Fisher emerged as Catherine's most public advocate and a resolute defender of the essential role of the pope as the successor of St. Peter in Catholic life. It was his detailed study that convinced Thomas More, former speaker in the House of Commons and briefly Lord Chancellor, to refuse to take the oath of kingly supremacy. More said that he was much influenced in his decision to accept the argumentation of Fisher by the fact that Fisher was such a holy man, such a person of integrity.

There is a background piece of information which is often forgotten today when we have been blessed with good popes for a long time. (We've been spoiled with really good popes for over a century; looking at the last 2,000 years, we're batting far above the average!) What we should remember when we're talking about Fisher and More is that for the whole of Fisher's lifetime, the best of the popes then — the best of the popes — were worldly, with limited religious enthusiasm, while some others had disgraceful private lives. In short, the papacy then was a scandal. But Fisher was prepared to die for the Catholic truth embodied in the papal office and not for the personal qualities of its officeholders.

Most historians have now abandoned the view that Catholicism in England on the eve of the Reformation was weak and corrupt because Henry and his Protestant successors had to wage a bitter struggle for generations to strangle Catholic life.

Martyrdom

Henry was regularly extravagant, and he was short of money from the beginning. In a masterstroke he commandeered the wealth of the monasteries not just for himself, but for many of the local nobility. In other words he locked most of the establishment behind him with significant financial encouragement!

In those days when there was little effective separation of powers and no freedom of speech, Henry would not tolerate public opposition. In April 1534, Fisher was confined in the Tower of London, and the case against him proceeded slowly. In May 1535, Pope Paul III created him a cardinal in the hope of saving his life. Henry VIII wasn't one bit impressed by that, declaring that Fisher would not have a head on his shoulders to wear the cardinal's hat. No head, no hat!

On June 22 of that year, Fisher was executed by beheading, rather than being hung, drawn and quartered, a remission which wasn't due to his age or office, but to his poor health. They were frightened that if they dragged him through the streets, he would die before he got to the execution spot. Despite his frailty, he announced in a loud voice that he was dying for the faith of the Catholic Church.

His headless, naked body was left on the scaffold until 8:00 p.m., when it was then placed in a shallow grave without ceremony. His head was boiled down and placed on London Bridge for two weeks, where his supporters were delighted by the fact "that it grew more florid and lifelike, so that many expected it would speak." His head was then thrown into the Thames to make way for the head of Thomas More. A calculated list of insults.

Incidentally Fisher's room in the Tower of London was renovated on Churchill's orders towards the end of World War II, not because of any reverence for Fisher's memory, but because if Hitler survived the War, Churchill was determined to imprison him, at least for a time, in the Tower of London.

Lessons to Be Drawn

Before I began my brief regime of St. John Fisher's life, I asked why we might ponder his story on a happy occasion like this commencement. This question has been left hanging, although the simple telling of his story suggests many lessons for a Catholic audience. Let me spell out a few further considerations.

A preliminary reason is that I, as a bishop, am keen to speak of a brave and farseeing fellow bishop who was fated to live in a violent time of change, which laid the foundations for England's rise to greatness and indeed the foundations of our contemporary English-speaking world.

Thomas More, the layman and martyr, Fisher's contemporary, has the best lines, is a more interesting personality and more humorous, and has gained much more publicity through the play and then the film, A Man for All Seasons. So, I want to redress this balance.

The Insight of Wisdom

St. John Fisher is remarkable for many reasons, but one might begin with a group of new graduates by reminding them that he was truly wise. I was very pleased to hear earlier what Joseph, your Class Speaker, had to say about wisdom. We know that wisdom is not coterminous with learning nor indeed with cunning. Wisdom brings insight, the ability to analyse and devise new syntheses, something akin to Cardinal Newman's criterion for an educated person, which is the ability to recognize the relative value of different truths. Wise people can evaluate public opinion, identify what is central, discard what is irrelevant, and downgrade what is secondary.

Cardinal Fisher was the only bishop to resist Henry, to acknowledge publicly that the issue wasn't merely a disputed annulment case, it wasn't just another quarrel with Rome, which would soon be over to enable the situation to return to normal. But many, many people believed those two things.

In fact, the rejection of the crucial role of the Papacy split the universal Church and set in train the destruction of Christendom. The subjection of the Church also opened the way to a royal despotism being exercised with fewer checks and balances.

A Life of Learning

A second point we should notice is that John Fisher was not only a learned man, but one who continued to study and learn throughout his life. In middle age he settled down to study Hebrew and Greek (not with an enormous amount of success, I believe), as well as wrestling with and answering the new challenges thrown up by the Protestant rebellion.

He was also a patron of learning, like the benefactors of this college and many other colleges, like the members of the Board of Thomas Aquinas College. As Chancellor at Cambridge University he worked to attract the funds necessary to bring leading scholars from abroad and to introduce the new learning of the Continental Renaissance, the rediscovery of the ancient classical authors in Greek and Latin, as well as the study of Hebrew for the Old Testament scriptures. He also played a major role in the establishment of Christ's College and St. John's College, new foundations at Cambridge, which are still thriving today.

An Example of Courage

St. John Fisher exemplifies also the importance of courage, of a principled integrity, a determination to speak the truth whatever the consequences. Courage is not universal, and every adult here knows that; indeed it is rare and wonderful, especially when the penalties, such as torture and execution, are extreme.

It is marginally easier to be courageous in a crowd, not merely because courage is infectious, but because friends, family, and intellectual allies are great helps in times of trial, bolstering morale and providing reassurance on judgments and tactics.

We should remember that Fisher and More were almost alone as they took their stand. As we have mentioned, no English bishop supported Fisher, and there was no family support whatsoever for More, not even from Meg Roper, his favorite daughter. They thought he was exaggerating the importance of the issue and was throwing away everything that they had for a mistaken point of view.

So, if courage is "grace under pressure," the pressures were not sufficient in Fisher's case to destroy the resolve of this sick, elderly bishop.

It might also be useful to state the obvious, even here at Thomas Aquinas College (and it's certainly not only useful, but it is necessary to make this point in Australia), and point out that Fisher and More (indeed the martyrs on both sides of the Reformation) did not die for conscience's sake, i.e. for the inviolability of personal conscience or the primacy of conscience. This is a contemporary way of speaking where public tolerance of different points of view is often regarded as the supreme virtue.

Fisher announced, as I mentioned, on the scaffold in a surprisingly strong voice, "Christian people, I am come hither to die for the faith of Christ's holy Catholic Church," and we well remember More's famous words that he was "the King's loyal servant, but God's first." They both died for the truth and more particularly the Catholic insistence on the essential role of the papacy.

A Model of Holiness

The final lesson we might draw from the life of St. John Fisher, and the most important one, is that we should be encouraged by his holiness, so that we imitate his faith and goodness, while we rejoice that we are not put to sterner tests.

Erasmus, one of the greatest scholars of the Renaissance and no religious zealot, described Fisher "as the one man at this time who is incomparable for uprightness of life, for learning, and for greatness of soul."

He was noted for the devotion he exhibited during the celebration of Mass, uniting himself with Christ's self-offering on the Cross. He had a replica of the severed head of John the Baptist on the altar in his episcopal residence, as he took very seriously indeed the teaching of Thomas Aquinas that the office of bishop requires a high degree of sanctity.

While all Catholics are not called to be priests or religious, all are called to follow Christ in a serious way, to imitate Christ's wholeness of life in what we traditionally call holiness. Fisher is a good model.

I wish all the graduands of Thomas Aquinas College my repeated congratulations on their graduation and hope they receive every appropriate grace and blessing as they commence their new lives.

I am sure that you have already met many good examples and mentors in this environment and in your families and among your friends. May you also be inspired by the learning, holiness, and courage of St. John Fisher to devote your own life to some great and some good cause.