- Home

-

About

Fidelity & Excellence

Fidelity & ExcellenceThomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

-

A Liberating Education

Truth Matters

Truth MattersTruth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

-

A Catholic Life

Under the Light of Faith

Under the Light of FaithThe intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

-

Admission & Aid

Is TAC Right for You?

Is TAC Right for You?Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

-

Students & Parents

Mind, Body & Spirit

Mind, Body & SpiritThere is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

-

Alumni & Careers

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Search

- Giving

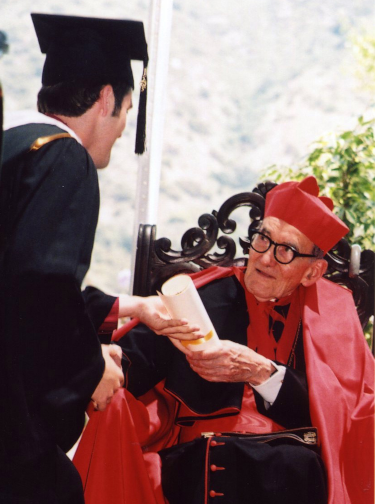

The 2005 Commencement Address by Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J.

For some years I have admired Thomas Aquinas College from afar, and therefore I feel particularly pleased to come here for this graduation. I sincerely thank your president and the members of the Board of Governors for having voted to give me the Saint Thomas Aquinas Medallion, which I shall treasure as a remembrance of these happy days.

For some years I have admired Thomas Aquinas College from afar, and therefore I feel particularly pleased to come here for this graduation. I sincerely thank your president and the members of the Board of Governors for having voted to give me the Saint Thomas Aquinas Medallion, which I shall treasure as a remembrance of these happy days.

The choice of a college is a very important decision in the life of any student. To this day I remain profoundly indebted to my own alma mater, completely different though it was from yours. I went to Harvard College from 1936 to 1940, where the curriculum, instead of being uniform, as it is here, was, one might say, wildly elective. But for that very reason I was able to choose tutors and courses that gave me a good grounding in the Western tradition of philosophy, theology, culture and politics. I studied Plato and Aristotle, Augustine and Aquinas, Luther and Calvin, and as a result I became a Christian believer and a Catholic, the best decision I have ever made. My entire adult life has been molded by what I learned in my college days, and I hope that you who are graduating today will be able to say the same sixty-five years from now.

A Moment of Grace

We live in a remarkable time. The forces of secularism and unbelief have never raged so furiously, but the Catholic Church is experiencing a special moment of grace. The eyes of the world have been turned for the past month on the city of Rome, which has lost one outstanding pastor and acquired another. All of you, I suspect, have followed these events: the unprecedented crowds of young people, the gathering of heads of state and chiefs of government, representatives of other churches and religions, and the omnipresence of journalists and television cameras. I personally was privileged to arrive in Rome before the burial of Pope John Paul II and to remain there through the installation of Benedict XVI. I shall never cease to cherish the memory of those historic days.

Both John Paul II and Benedict XVI exemplify the value of education. They are men in whom faith and reason have met and carried the human spirit to lofty heights. John Paul II was a philosopher who had earned a doctorate in theology; Benedict is a theologian thoroughly versed in philosophy. Both of them have assimilated the intellectual history of the West in its manifold expressions. Both have been university professors; each has authored at least a dozen books. The election of these two great intellectuals to the office of Peter shows the extreme importance that the Catholic Church today attaches to the life of the mind.

We live in a time of conflicting cross currents. Many of our contemporaries are rejecting the great intellectual heritage on which the civilization of Europe was built. Some no longer believe that the world owes its existence to a beneficent Creator, that there are any objective standards of right and wrong, or that human beings are made for eternal life. Every doctrine of Christian and Catholic faith is being subjected to relentless attack, and for this reason it is essential to have in the Church leaders who can persuasively articulate the grounds of faith. Not every priest or bishop is able to do so, but we are fortunate to have at the helm of the universal Church leaders equal to this task.

The Church in America

The Church in the United States has always had, and continues to have, an exceptionally close relationship to Rome. Our bishops constantly rely on directives from the Holy See to solve questions disputed here at home. Our country is extremely vast. The Catholic Church is multiethnic, multiracial, multicultural, and multilingual. We have 169 dioceses and any number of religious orders and societies of consecrated life. For all these reasons there is no one who can speak or make decisions for the Church in the United States. The Conference of Catholic Bishops is a useful organ for consultation, but it has practically no authority over the member bishops. When the bishops cannot reach a consensus, they regularly turn to Rome for help. Even the appointment of bishops comes not from the United States but from Rome. On issues of doctrine and discipline, the supervision of the Holy See is indispensable. Without that supervision, the Catholic Church in our country would be much more divided than it is.

Rome also keeps the Church in the United States in union with the Catholic Church in other countries. Universality or catholicity is one of the greatest blessings we have. It is almost unique to our communion. The Orthodox Church of America is only tenuously linked to the patriarchates of Constantinople and the autocephalous churches of Eastern Europe. The American Episcopal Church is almost totally independent of Canterbury. The Lutheran and Calvinist Churches are unable to look to Geneva or any seat of authority that can speak for their denominations as a whole. The indigenous churches of America are all too much at home in our culture. They find it difficult to maintain continuity with the Fathers and Doctors of the past and meaningful union with Christians of other lands. They are deficient in the apostolicity and catholicity that are they still confess in the creed as properties of the Church.

Some would want the Catholic Church in our country to become more autonomous. But if their wishes were followed, we would be in great danger of isolation from fellow believers elsewhere. We Catholics attach great importance to solidarity in faith and sacramental life with our coreligionists of all centuries and all nations. Rome is the center and touchstone of unity.

Time after time, down through the centuries, Rome has restrained Catholics from forming national schismatic bodies, as the Gallicans tried to do in France, and similar groups in other nations. The national churches that were formed in past centuries are break-off groups that no longer have a future. They are like branches cut off from the true vine.

The Popes and “Americanism”

For two centuries and more, the Popes have been like fathers to us American Catholics. They have encouraged and supported us, sent missionaries to our shores, nourished us with sound doctrine, and occasionally intervened to save us from ourselves.

We Americans do not like to be criticized or corrected from abroad, but sometimes we need such treatment. A paramount instance was the letter of Pope Leo XIII, Testem Benevolentiae, issued in 1899. The letter condemned a tendency known as “Americanism,” which was affecting some of the faithful in this country. These Catholics were maintaining that the Church in America ought to be different than it was in the rest of the world. They were calling upon Church authorities to relax their teachings, to accommodate to the spirit of the age, and make concessions to new opinions. In particular, they recommended that individual Catholics should be left free to follow their own judgment, to embrace whatever opinions they pleased, and to promote any ideas that appealed to them. Men and women of our time, according to this view, have come of age and should not bow down to any external authority. Instead of cultivating passive virtues such as humility and obedience, they should actively assert themselves. The religious life, with its vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, was particularly called into question.

The Pope’s Ministry of Unity

Catholics in this country protested that Americanism was only a “phantom heresy.” Indeed, it was not a full-blown heresy, but it might have become such had the Pope not intervened. We should be grateful that he does exercise a fatherly oversight over the Church in this country, as in others. That is an essential aspect of his ministry of unity.

I am not certain that we need such supervision more than other countries. But we surely have to be on guard against a false spirit of liberty. Because our nation was founded upon a Declaration of Independence, it is all too easy for American Catholics to imagine that our church ought to be independent of any higher authority, especially in Europe. But to call for autonomy is often the first step in a process of dissolution. Unshackled from Rome, the Catholic Church in this country would be more easily manipulated to conform to the spirit of the age. The dominant culture is hostile to many Christian values. It is predicated on the pursuit of wealth, pleasure, and success, all understood in highly individualistic terms.

From John Paul II to Benedict XVI

John Paul II pointed out these dangers and shortcomings, especially in his critique of consumerism. His death will not lead to a shift in doctrine. As Prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Ratzinger was closely associated with all the doctrinal pronouncements of Pope John Paul.

Inevitably, the death of so great a Pope leaves a vacuum. He was in a sense the moral leader of the world. No other figure, I believe, was so generally admired and loved. We all have to adjust to the absence of his genial smile and playful humor and the cessation of his firm and creative pastoral initiatives. Perhaps those of us who are of my generation will find the adjustment easier than you, who have known no other Pope. In my lifetime there have been eight Popes: from Benedict XV to Benedict XVI — and I expect to be still around for a few more papal elections. My paradigm for the papal ministry was set by Pius XII, who was Pope for the first eighteen years of my life as a Catholic. He did much to prepare for the renewal of Vatican II, to engage the Church in the defense of human rights, and to protect Jews and others in the tragic days of the Holocaust.

What will the new Pope do and be? I cannot imagine that he will try to imitate the style of John Paul, who was inimitable. He will have to be himself. But in his new office he will not act simply as a prefect of doctrine. He will perhaps put on a new persona as the universal pastor of Christ’s flock. From his initial homilies and speeches it appears that he will continue the policies of his predecessor. He will carry through the Year of the Eucharist, including the World Youth Day of August and the assembly of the Synod of Bishops in October, both of which will have a Eucharistic focus. He will maintain the new evangelization, ecumenism, and interreligious dialogue as high priorities. He will uphold the culture of life. And like John Paul II, he will champion reason as an indispensable friend of faith. Opposing what he calls the dictatorship of relativism, he will confidently proclaim the universal lordship of Jesus Christ.

Our Free Assent and Willing Cooperation

However brilliant and eloquent a pope may be, however sound his initiatives, he cannot renew the Church by his own unaided efforts. His authority is pastoral, not coercive. He can only call for free assent and willing cooperation. But if we love the Church, we shall deliver that response. Instead of setting ourselves above the Vicar of Christ as if we were his judges, we shall allow him to teach and correct us. A church that taught only what we already believed would be of no use whatever. As G. K. Chesterton wrote, we need a Church that is right not only when we are right but especially when we are wrong.

The Church in our nation is bustling with activity. It is vibrant but tossed about by many winds of doctrine. Those of you who are graduating from Thomas Aquinas College today can be a stabilizing influence. You have been exposed to a long tradition of wisdom, much of it inspired by divine revelation. Your minds have been honed by assiduous study of the arts and sciences. The Church counts on you to make a mature and responsible contribution as Christians in the Church and in the public square. When so many others are spreading cynicism and advocating unwise reforms, you will see more deeply into the real issues that are at stake. You can be leaders of your generation in shaping the future of the Church and of the nation. May God inspire, bless, and prosper your ways!