- Home

-

About

Fidelity & Excellence

Fidelity & ExcellenceThomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

-

A Liberating Education

Truth Matters

Truth MattersTruth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

-

A Catholic Life

Under the Light of Faith

Under the Light of FaithThe intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

-

Admission & Aid

Is TAC Right for You?

Is TAC Right for You?Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

-

Students & Parents

Mind, Body & Spirit

Mind, Body & SpiritThere is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

-

Alumni & Careers

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Search

- Giving

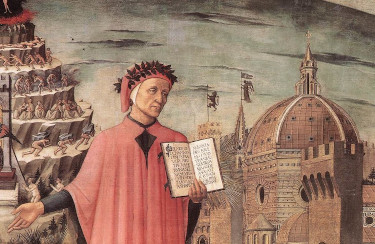

The Poet of Catholic Liberal Education

Why We Study Dante Alighieri

By Dr. Brian T. Kelly (’88)

Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean Brian T. Kelly’s report to the Board of Governors at its May 13 meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks in which Dr. Kelly explains why the College includes certain authors in its curriculum.

In the early cantos of the Inferno, Dante suggests that he is one of the six greatest poets of all time. This might sound like hubris, but many would suggest that he is too modest here.

In the early cantos of the Inferno, Dante suggests that he is one of the six greatest poets of all time. This might sound like hubris, but many would suggest that he is too modest here.

The Italians know him simply as “the poet.” T.S. Eliot lays down the bold claim that “Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them; there is no third,” and further that Dante is “a model for all poets.” It is the assessment of many that the Divine Comedy is the most magnificent poem ever written. Eliot asserts that the final canto of the Paradiso “is the highest point that poetry has ever reached or ever can reach.”

And what other poet is the subject of one papal encyclical and the inspiration for another? Indeed, in 1921 Pope Benedict the XV issued In Praeclara Summorum, devoted exclusively to praising the great Florentine, and Benedict XVI has said that Dante inspired him to compose his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, on love.

If Dante had never written his masterpiece, the Divine Comedy, he would still be considered a great lyric poet. His early La Vita Nuova is delightful. This slim volume contains courtly love poems in the early troubadour style, focusing on a recently deceased young lady, Beatrice, whose beauty, grace, and virtue had pierced Dante’s heart. Dante’s love for Beatrice has confounded many, but is at the center of almost all of his writings. It is not a lustful desire but a purifying admiration. When Dante strays from the path of wisdom and virtue, he sees this as a departure from his idealized love of Beatrice. His commitment to her beauty and virtue is a sort of bridge to divine beauty and nobility.

There was no conflict between his total love for Beatrice and his love for and commitment to his own wife, Gemma. You can see that this love can be very difficult to grasp, but we as Catholics have an advantage since our devotion to Mary is this sort of love, a love that calls us to cling to her Son, the Word Incarnate.

The Divine Comedy

Indeed, Ralph McInerny, in his final book, Dante and the Blessed Virgin, argues that “Mary is the key to Dante.” We see these loves intertwined in the beginning of the Inferno, when Dante has lost his way and Mary, through St. Lucy, sends Beatrice to call Dante back to the path of righteousness. To do this more effectively Dante must travel through and experience Hell, and then Purgatory, and finally Heaven. Here he will see firsthand the effects of man’s choices on earth and ask questions of the damned and the elect.

This obviously gives the imaginative poet and storyteller great material to work with, and he draws on the length and breadth of Scripture, pagan and Christian literature, theology, philosophy, history, and his own times. In Hell we meet Judas, Caiaphas, Brutus and Cassius, Odysseus, Mohammed, Medusa and the Minotaur, numerous wicked popes and some of Dante’s own friends and relatives. We also find a number of the authors we read at the College, including Aristotle, but these are in the relatively mild Limbo.

As Dante travels through Purgatory and eventually Heaven, he is cleansed of his sinfulness and drawn into a greater understanding of God’s wisdom. He inquires about theological matters with the greatest saints and ultimately glimpses a vision of the Trinitarian Godhead. There is a sweet episode in which St. Bonaventure, the great Franciscan, sings the praises of St. Dominic, and St. Thomas Aquinas sings the praises of St. Francis of Assisi. In Heaven there is no longer any contention between these great orders.

It is hard to even begin to sketch the poem in a way that fairly represents its depth and richness. Think about what a great painting can capture in a moment, as it were. Think of what a beautiful poem can accomplish in a matter of 20 or 30 lines. Then think of what one of the greatest poets of all time can accomplish in 14,233 lines. In the sophomore seminar we spend six weeks reading the Divine Comedy. I take it as more or less obvious that this work demands the time and attention we give to it.

I would like to draw out two things that make Dante especially delightful for us and essential reading for the world: first, Dante’s education and second, his deep Catholicism.

The Poet’s Learning …

First, Dante’s trip through the afterlife is remarkable in that it displays a solid formation in the liberal arts, in philosophy and the sciences, and in all of these as ordered to theology. Dante is a liberally educated man, and his poetry incorporates reason and argument without abandoning poetry’s fundamental aim of moving and cleansing the emotions.

As a young man Dante proved skillful as a poet, finding his great theme of love and his muse, Beatrice. But he recognized his inadequate formation; he could not do justice to this noble theme. He had already studied the best poets, but if he was to create an epic poem of profound depth and wisdom he needed to know more. In the midst of an explosive political career, Dante took time to pursue the breadth of learning available in the late 13th century. He read Aquinas and Bonaventure, Augustine and Boethius, Aristotle and Plato, Averroes and Avicenna, and even lesser figures like Roger Bacon and Siger of Brabant. In other words Dante went back to school to get a good liberal education.

Through the years we have heard versions of this story from so many of our students. Sometimes, even with advanced degrees in hand, they have realized that to live up to their potential and calling they needed a liberating education. They needed the kind of formation that would help them to make a good beginning on the road to wisdom. And the power of this education is on display in the Divine Comedy. This work is a strong argument for the real value of liberal education.

… and the Poet’s Faith

I also wanted to talk about Dante’s Catholicism. Here I will just look to In Praeclara Summorum, an encyclical issued by Pope Benedict XV, honoring Dante on the sixth centenary of his death. The Holy Father is effusive in his praise: “Among the many celebrated geniuses of whom the Catholic faith can boast … and to whom civilization and religion are ever in debt, highest stands the name of Dante Alighieri.” He goes on to speak of the Divine Comedy as “a teaching for men of our times” and as “a treasure of Catholic teaching.”

How is it that Dante can be said to teach modern man? This poem is an enormously great and attractive work of art. But it cannot be read and savored without in some way inhabiting and forming some sympathy for the worldview it embodies. And Dante’s worldview is thoroughly Catholic. Even the geography and arrangement of Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory reflect a thoroughly Catholic mind nurtured on the rich theological, intellectual tradition of the Church. For the unbeliever it can be quite a challenge to adjust to the world that he finds in the Divine Comedy. But as the unbelieving mind adjusts, it cannot but be a little bit opened to the truths of the Faith. In coming to love and appreciate the beauty of the poem, the reader is in some small way initiated into the mysteries.

Pope Benedict XV insists that this is a matter of experience. He says, “we know now too how … many who were far from … Jesus Christ, and studied with affection the Divina Commedia, began by admiring the truths of the Catholic Faith and finished by throwing themselves with enthusiasm into the arms of the Church.”

So Dante’s great book is a wonderful apologetic; by its beauty and clarity and total commitment it invites nonbelievers to come home. Pope Benedict XV ends this wonderful encyclical by speaking, as it were, to us, “And you, beloved children, whose lot it is to promote learning under the Magisterium of the Church,” (that’s us!) “continue as you are doing to love and tend the noble poet whom We do not hesitate to call the most eloquent singer of the Christian idea. The more profit you draw from study of him the higher will be your culture, irradiated by the splendors of truth, and the stronger and more spontaneous your devotion to the Catholic Faith.”