By Dr. Brian T. Kelly (’88)

Note: The following remarks are adapted from Dean Brian T. Kelly’s report to the Thomas Aquinas College Board of Governors at its February 12, 2010, meeting. They are part of an ongoing series of talks in which Dr. Kelly explains why the College includes certain authors in its curriculum.

Board Member Henry Zeiter, chairman of the Committee on Academic Affairs, recommended that I pick out some work that we read in the College’s academic program and take a few minutes to explain why we read that work or that author. Since Dr. Zeiter’s interests bend so much toward the theological, I decided to say a few words about why we read St. John Damascene. This seems like a fair question because we are named for and aim to be serious disciples of St. Thomas Aquinas. Why, then, take time — roughly a month at the end of sophomore year — to read Damascene when we could be reading more of our beloved patron?

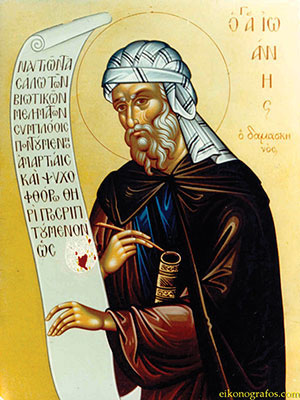

A few words about St. John: He was born in the late 7th century and died in the late 8th entury. He was not a revolutionary innovator but an encyclopedic compiler of traditional Catholic doctrine. He has been called the last of the Greek fathers as well as the first of the scholastics. His greatest work, The Fountain of Wisdom, was the first attempt at a summa theologica, or summary of all theological wisdom. This book is perhaps as important in the East as Thomas’ Summa Theologiae is in the West. St. John is famous for defending the use of images and relics against the iconoclasts and for laying the theological groundwork for the doctrine of Mary’s assumption.

A short answer as to why we read St. John would be that we read him because St. Thomas read him. And this immediately suggests that he is worth reading in his own right.

It was by reading St. John Damascene and others that a young Thomas Aquinas began to make inroads toward understanding what the human mind can grasp about the Trinity, about the procession of the Word, and His subsequent Incarnation. These are very difficult topics, and sometimes it helps to wrestle with the foundations of these teachings just as St. Thomas did. (To tell the truth, we cheat a little in our studies, and after struggling with Damascene’s account of the Hypostatic Union, we do in fact read a small section of Aquinas’ treatment, where he speaks with startling clarity and penetrating insight.)

Two other reasons spring to mind as to why we find it worthwhile to read St. John Damascene. First, he is noted for declaring and defending Mary’s title as the “Mother of God,” the Theotokos. This is a very rich topic and very important for the Church in our times. St. John goes so far as to say that when we call Mary “Mother of God,” we express the whole truth about who Jesus Christ is.

Secondly, it is important for our students to meet — and in some way savor — the richness of the East. The split between the East and the West is one of the great tragedies of Church history. In reading St. John Damascene, our students taste this richness of Eastern thought in a way that calls out for unity, in a way that points out the fundamental unity of doctrine in the whole Church.

Indeed, Pope Leo XIII, who in many ways inspired the foundation of this College, declared St. John “Doctor of the Universal Church” in December of 1890. More recently, Pope Benedict XVI praised him extensively in his Wednesday Audience on May 6 of 2009.