- Home

-

About

Fidelity & Excellence

Fidelity & ExcellenceThomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

-

A Liberating Education

Truth Matters

Truth MattersTruth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

-

A Catholic Life

Under the Light of Faith

Under the Light of FaithThe intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

-

Admission & Aid

Is TAC Right for You?

Is TAC Right for You?Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

-

Students & Parents

Mind, Body & Spirit

Mind, Body & SpiritThere is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

-

Alumni & Careers

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?

What Can You Do with a Liberal Education?Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Search

- Giving

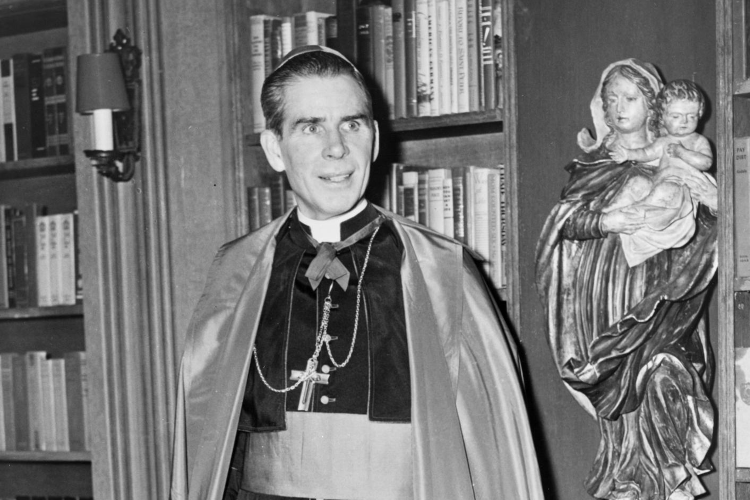

On His 125th Birthday: Ven. Fulton Sheen on Catholic Higher Education

Today marks the 125th birthday of the Venerable Fulton J. Sheen, the late and beloved prelate, evangelist, and television pioneer. As such, it’s a fitting occasion to recall the Archbishop’s scathing critique on the elective/major system, which, in his view, crippled Catholic higher education — and which continues on most campuses to this day.

On his Life is Worth Living television show, which aired from 1952 to 1957, His Excellency offered the following assessment (adapted as an essay in his 1953 book of the same name):

In every college curriculum, some courses are more important than others. Here, we repeat, we are not speaking of vocational or professional training, but rather of general or liberal education. Courses should be arranged in a pyramid.

The ancient Greeks illustrated the hierarchy of sciences by naming the three superior subjects of the mind.

The principle which guided them is still valid, namely, every superior subject illumines the lower one. If you pour water on top of a pyramid, it slowly seeps down on the ever-widening base. So the principles of metaphysics shed some light on mathematics; mathematics aids the knowledge of the universe; it also helps clarify music. In a musical composition, not every note has exactly the same stress; in language, not every word has the same emphasis; and in education, not every course has the same value.

Today the pyramid theory of education is replaced by the shelf theory. On a shelf are a number of bottles. The assumption is that when you go to college, it does not make any difference what course you take; you select any course that pleases your fancy. At the end of four years, you have collected sixty-four bottles, or sixty-four credits. It does not make a particle of difference what is in the bottles: sand, water, milk, Spanish, rug collecting, economics, or football coaching. They all have equal value. Bring them to the Dean, and you get a sheepskin.

The result is that students are not getting the education they ought to receive; they get only a congeries of unrelated, disconnected, and disjointed subjects, which they and no one else can put together. An encyclopedia is not educated, despite its bursting [with] knowledge, because it lacks the power to coordinate one subject with another. A truly educated man, on the contrary, sees a relationship between subjects, as he sees coordination in his own body and the universe.

Any system of electives which ignores the unity of knowledge and the overall purpose of life confuses the student rather than perfects him in truth.

The founders of Thomas Aquinas College would echo this critique in the College’s founding and governing document, A Proposal for the Fulfillment of Catholic Liberal Education (1969):

Since few educators were prepared to defend the proposition that one course of instruction might be of itself more educative than another (or the proposition that there is a discoverable order among the existing disciplines), no one was able to resist the deluge of course proliferation which created the modern college catalogue. Indeed, few spoke out against it, and there were those who maintained that the student’s academic freedom had, in a significant sense, been enhanced by the multiplication of options set before him. Until the anarchic events of the late nineteen sixties, few seemed to realize the potentially disastrous consequences of the principle that the student himself is the best judge of which studies are most relevant to his intellectual development. Nor was it noticed how undergraduate dialogue would be restricted by full specialization of interests on the part of both faculty and student body.

Indeed, an authentically Catholic and liberal education, the founders continued, “demands that all the parts of the curriculum not ordered to technical concerns should be conducted with a view to understanding the Catholic faith, and that the Faith itself should be the light under which the curriculum is conducted.” Such is precisely the sort of College they established, with its single, integrated curriculum ordered to the study of theology.

No wonder, then, that when the founders staged a promotional dinner in support of Thomas Aquinas College just 18 months before it first opened its doors, Archbishop Sheen graciously served as the keynote speaker.

Venerable Fulton J. Sheen, pray for us!